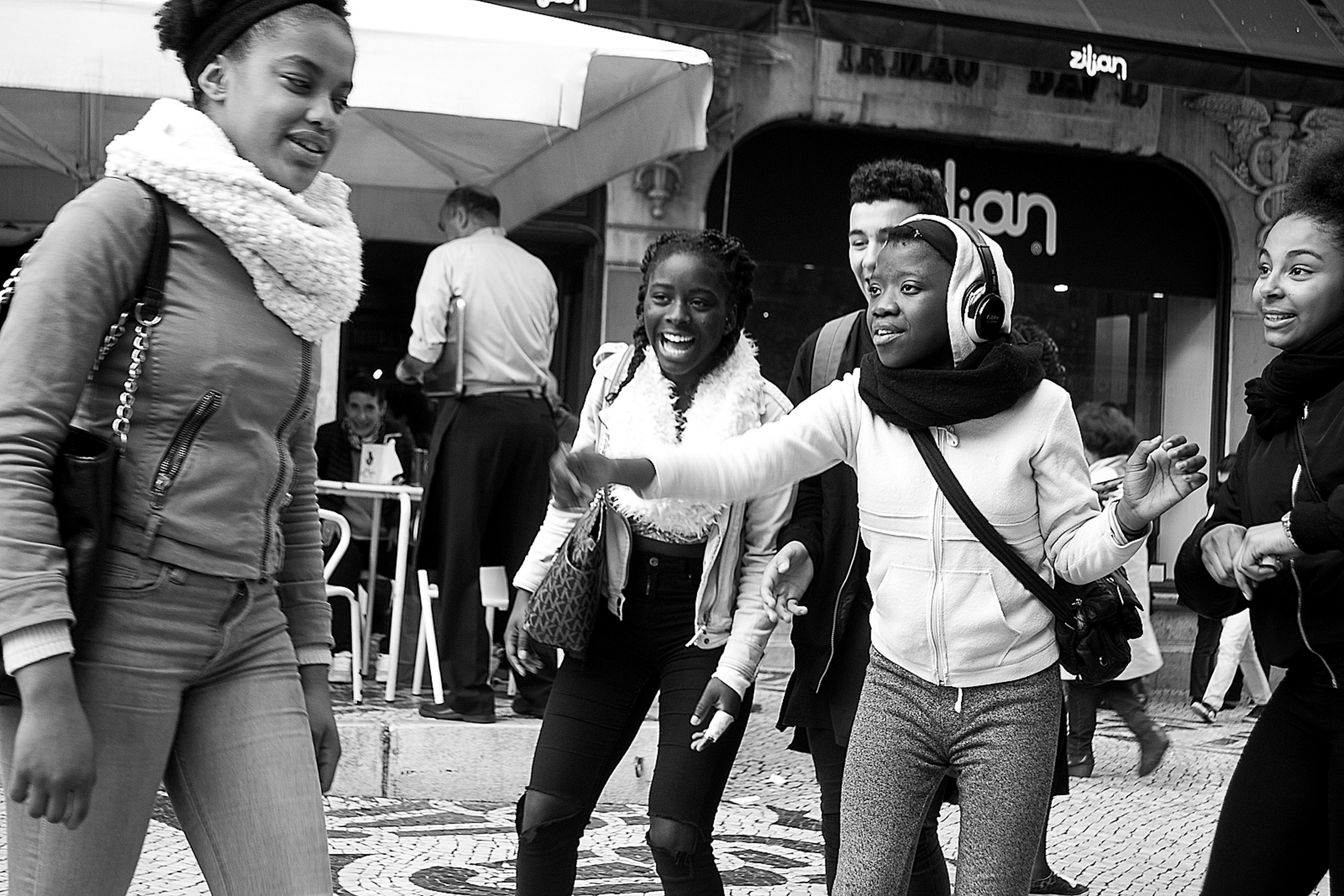

Publicada em 2020, é uma série em preto-e-branco de pessoas negras anônimas em momentos espontâneos nas ruas de Lisboa, onde o autor realizou residência artística três anos antes. De forma poética e ao mesmo tempo contundente, o trabalho toca em questões relacionadas à invisibilidade do negro na fotografia portuguesa, ao racismo estrutural e ao silenciamento ao redor do tema. A publicação foi pensada como uma espécie de encarte de “Lisboa, cidade triste e alegre”, de Victor Palla e Costa Martins, uma das obras mais importantes da fotografia lusitana. As imagens dialogam com os versos de Agostinho Neto, Carla Fernandes, Francisco José Tenreiro e Telma Tvon.

Para comprar: RV Cultura e Arte

*

Published in 2020, it is a black-and-white series of anonymous black people in spontaneous moments on the streets of Lisbon, where the author held an artistic residency three years earlier. In a poetic and at the same time blunt way, the work touches on issues related to the invisibility of black people in Portuguese photography, structural racism and the silencing surrounding the topic. The publication was designed as a kind of insert for “Lisbon, a sad and happy city”, by Victor Palla and Costa Martins, one of the most important works of Portuguese photography. The images dialogue with the verses of Agostinho Neto, Carla Fernandes, Francisco José Tenreiro and Telma Tvon.

For sale: RV Cultura e Arte

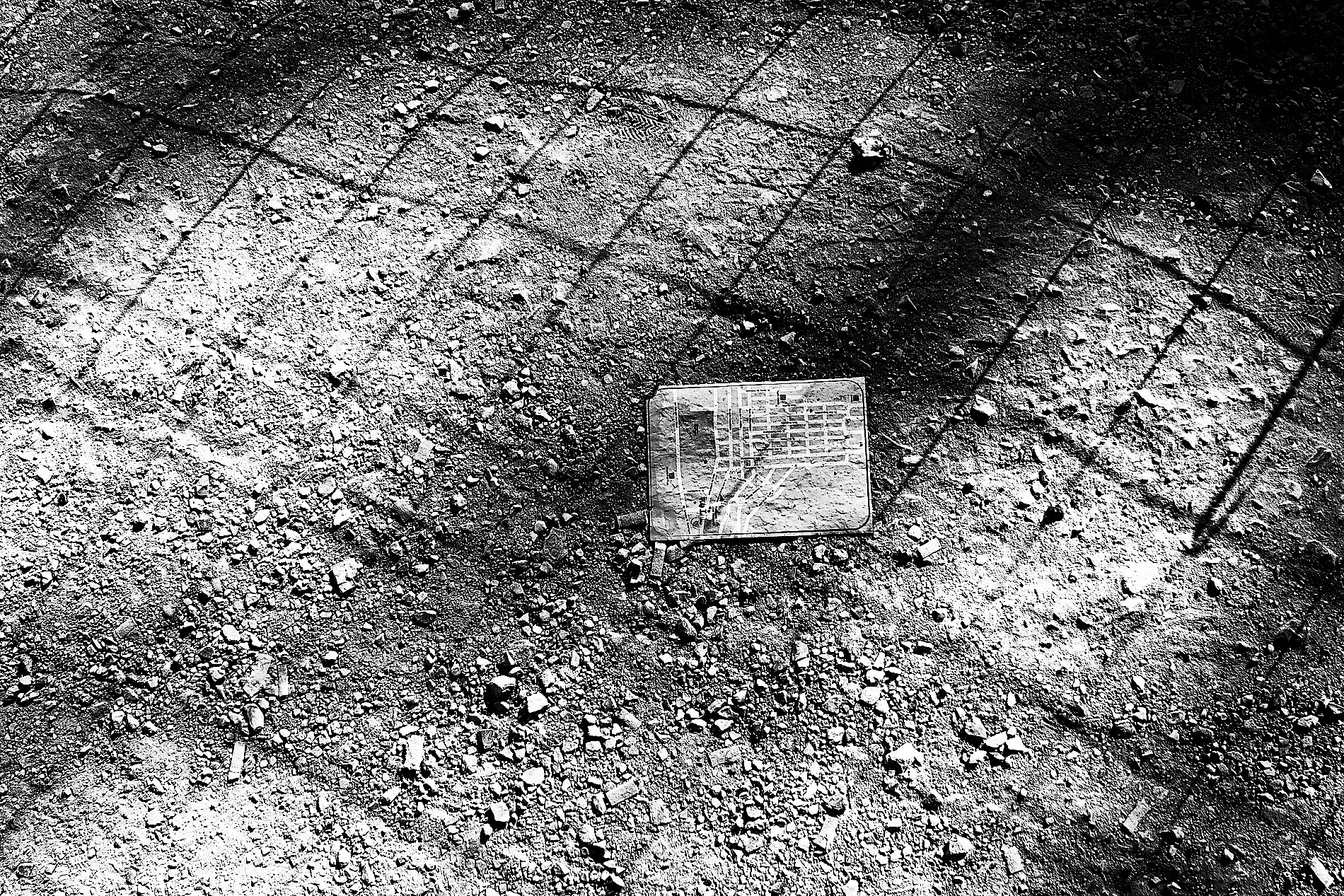

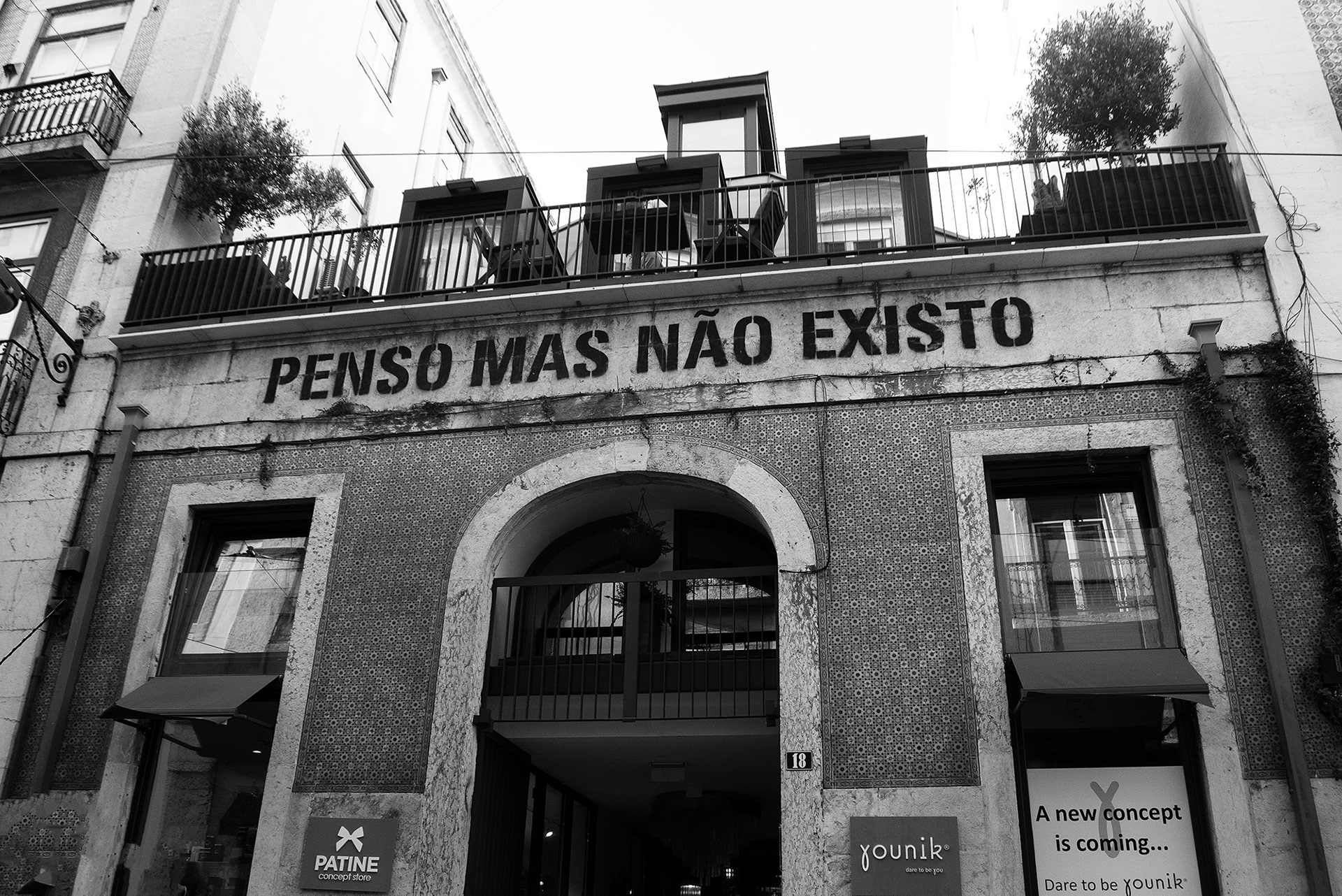

Durante quase dois meses ando a esmo pelas ruas de Lisboa. Entre janeiro e março, o frio e a chuva são intensos, os ossos doem. Os poucos dias de sol e luz são revigorantes. A língua oficial é cosmopolita: idiomas do mundo inteiro circulam nos eléctricos, ocupam as ruas do Chiado, invadem o Mosteiro dos Jerônimos. Cidade fixe onde as pessoas fazem contato visual, numa saudação muda e cálida, sem excesso. Salvador está presente a todo instante: contrastes e semelhanças, saudade e repulsa, fluxo-refluxo enviesado de um lado a outro do Atlântico. Flanar sem destino, vagar fotografando: a forma de descobrir o que se apresenta de mais intrigante.

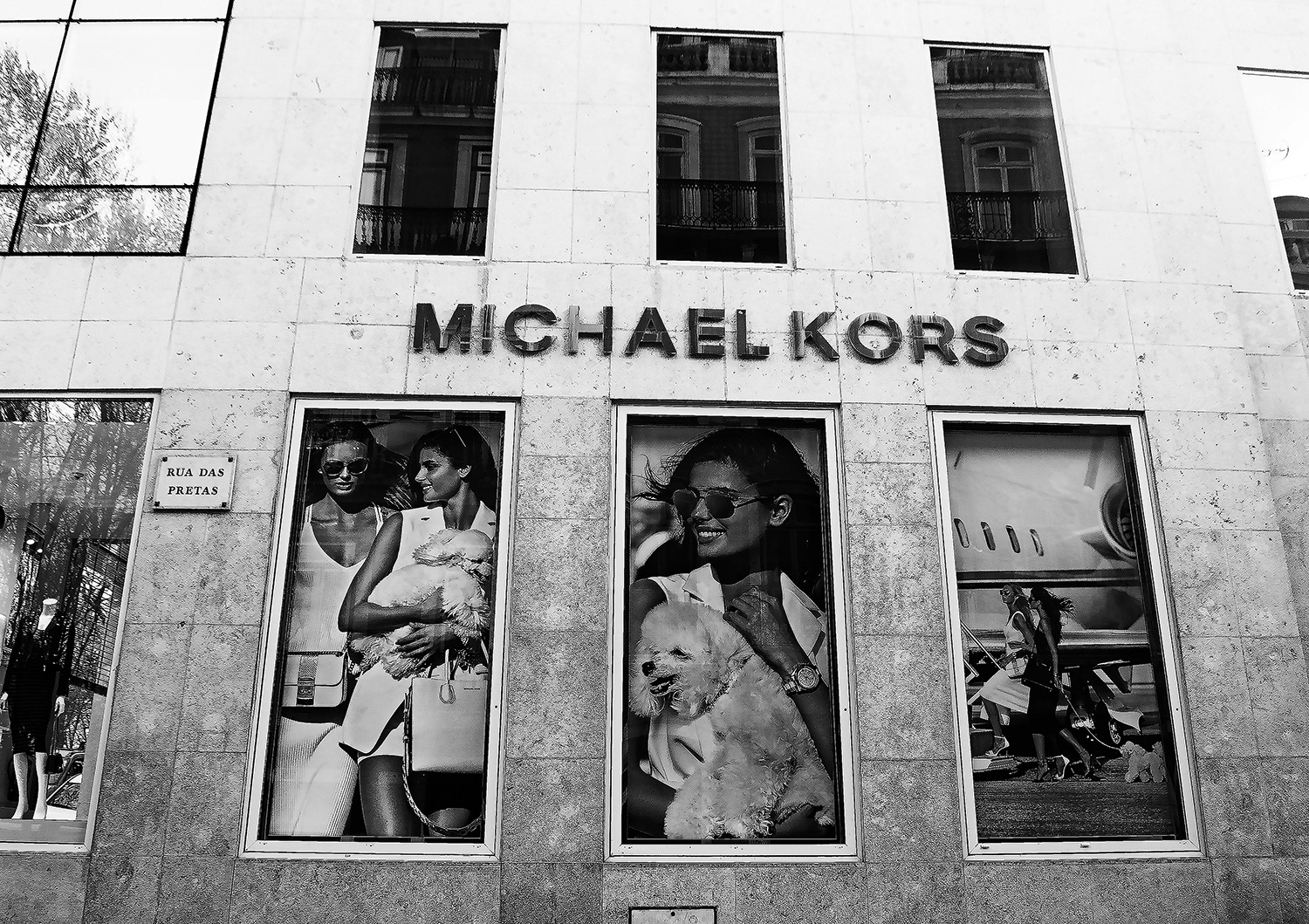

Percebo como são raros os negros onde há a presença massiva do turismo. Deslocados em seu não lugar, permanecem invisíveis ao olhar estrangeiro. Nos sítios onde mais circulo, Praça da Figueira, Rossio, Praça D. Pedro IV e também no Largo São Domingos, onde um memorial evoca o massacre de milhares de judeus, em 1506, noto a explícita separação: de um lado, vários grupos de turistas bebem ginjinha; do outro, a algaravia dos imigrantes que conversam com entusiasmo. Observam-se de longe. Não se misturam. Não parece haver disposição para o diálogo.

Sento-me em um dos bancos onde os africanos se concentram. Ao perceber que tento fotografá-los, um senhor, alertado por outro, me interpela. “Cá não podes fazer isso”, diz com firmeza, mas sem rispidez. Peço desculpas. Mostro a câmera desligada (alguns registros já haviam sido feitos). Na foto clandestina, ele aparece apontando um lugar vago, como se dissesse aos intrusos como eu: “fora daqui”. Evitei que ele tivesse o rosto identificado. Era o mínimo que eu poderia fazer para respeitar o seu direito. Sendo ele, eu teria feito o mesmo: afinal, quem é você, estranho, por que deseja me fotografar, o que pretende fazer com a minha imagem?

No largo do Intendente, visito a primeira mostra de um fotógrafo português que ainda se considerava amador. Desanimado, vejo emolduradas as vielas de Alfama, idosos contemplativos em suas janelas, roupas estendidas em varais suspensos ao longo das fachadas; becos e escadarias em luz e sombra. Claro que não havia negras ou negros na exposição.

Em mais um dia sem rumo, mudo de calçada na rua da Palma e descubro por acaso o Arquivo Municipal Fotográfico. Entro. Em cartaz, os Yanomami de Claudia Andujar. Na sala de pesquisa, desejo me deparar com um Ferrez ou um Gaensly em versão lusitana. A atendente, muito solícita, diz que não há registros de negros, que seria difícil encontrar esse tipo de imagem. Por sua indicação, ainda vasculho virtualmente todo o acervo do Centro Português de Fotografia, que fica no Porto. Nada encontro.

Durante uma aula com José Soudo, folheio o fotolivro mais importante de Portugal: "Lisboa, cidade triste e alegre", de Costa Martins e Victor Palla, publicado em 1959. Pergunto por que é tão raro encontrar negros retratados pela fotografia portuguesa. “Sim, é difícil. Sei que naquela época [do regime salazarista], os negros eram considerados como não pessoas”, ele responde.

Do alto do miradouro São Pedro de Alcântara, a vista é muito gira. O vento gelado é cortante, castiga a pele. Turistas alheios, de habituais feições apalermadas, carregam vistosas leicas penduradas no peito e fotografam os casarios iluminados pelo sol de inverno. Não menos invisível, circulo ao lado deles recordando as palavras do mestre Soudo. Penso que a depender da direção que se aponte as objetivas, continuaremos todos não sendo. Pessoas.

*

For almost two months I wandered the streets of Lisbon. Between January and March, the cold and rain are intense, the bones hurt. The few days of sun and light are invigorating. The official language is cosmopolitan: languages from all over the world circulate on trams, occupy the streets of Chiado, invade the Jerónimos Monastery. Cool city where people make eye contact, in a silent and warm greeting, without excess. Salvador is always present: contrasts and similarities, nostalgia and repulsion, biased reflux from one side of the Atlantic to the other. Flirting aimlessly, walking around photographing: the way to discover what is most intriguing.

I realize how rare are blacks where there is a massive presence of tourism. Displaced in their non-place, they remain invisible to the foreign eye. In the places where I most circle, Figueira, Rossio, D. Pedro IV Square and in São Domingos, where a memorial evokes the massacre of thousands of Jews in 1506, I note the explicit separation: on the one hand, several groups of tourists drink ginjinha; on the other, the gibberish of immigrants who talk with enthusiasm. They are observed from afar. They don't mix. There does not seem to be a willingness for dialogue.

I sit in one of the banks where Africans are concentrated. When I realize that I try to photograph them, a man, alerted by another, challenges me. “You can't do that here,” he says firmly, but without harshness. I apologize. I show the camera off (some records have already been made). In the clandestine photo, he appears pointing to a vacant spot, as if to say to intruders like me: “get out of here”. I prevented him from having his face identified. It was the least I could do to respect your right. Being him, I would have done the same: after all, who are you, stranger, why do you want to take a picture of me, what do you intend to do with my image?

In Largo do Intendente, I visit the first exhibition of a Portuguese photographer who still considered himself an amateur. Discouraged, I see the alleys of Alfama framed, contemplative elderly people at their windows, clothes hanging on clotheslines suspended along the façades; alleys and staircases in light and shade. Of course, there were no blacks or blacks in the exhibition.

On another day without a destination, I change sidewalks on the Palma Street and happen to discover the Municipal Photographic Archive. I enter. On display, the Yanomami by Claudia Andujar. In the research room, I want to come across a Ferrez or a Gaensly in Portuguese version. The attendant, very solicitous, says that there are no records of blacks, that it would be difficult to find this type of image. For your indication, I still search virtually the entire collection of the Portuguese Center of Photography, which is in Porto. I find nothing.

During a class with José Soudo, I leaf through the most important photobook in Portugal: Lisbon, a sad and happy city, by Costa Martins and Victor Palla, published in 1959. I ask why it is so rare to find black people portrayed by Portuguese photography. "Yes, it is hard. I know that at that time [of the Salazar regime], blacks were considered to be non-people”, he replies.

From the top of São Pedro de Alcântara viewpoint, the view is very gira*. The cold wind is sharp, punishes the skin. Foreign tourists, with usual appalling features, carry showy leicas hanging from their chests and photograph houses illuminated by the winter sun. No less invisible, I circle beside them remembering Master Soudo's words. I think that depending on which direction the objectives are aimed, we will all still not be. People.

[*] Portuguese slang that means “beautiful”

*